|

“Resettlement” in Sooripuram |

Introduction

During the civil war’s final phases, more than 300,000 people were displaced; the majority of those internally displaced persons (IDPs) were eventually relocated to IDP camps – with Menik[1] Farm[2] (Vavuniya) being the largest IDP camp. The conditions in Sri Lanka’s IDP camps were – to say the least – substandard. Attempting to deflect international pressure, the Government of Sri Lanka closed Menik Farm in September 2012.

At that time the United Nations (UN) noted its “concern”[3] for the people of Keppapilavu (Mullaitivu) – since they were still unable to return home, as the military still occupied their land. (Community members had been told that they would be going “home,” but soon found out that, in this case, “home” in Sri Lankan military vernacular meant “Sooripuram.” Community members from Keppapilavu were relocated to Sooripuram so that the Government of Sri Lanka could announce the closure of Menik Farm; they were never allowed to go home).

Recently, a fifty-year-old woman told TSA that, since Sooripuram is located next to Keppapilavu, she sees her cattle from her makeshift Sooripuram home on a daily basis. This is a stark reminder of what she had more than four years ago, but what she may never regain again.

Recent Events in Keppapilavu

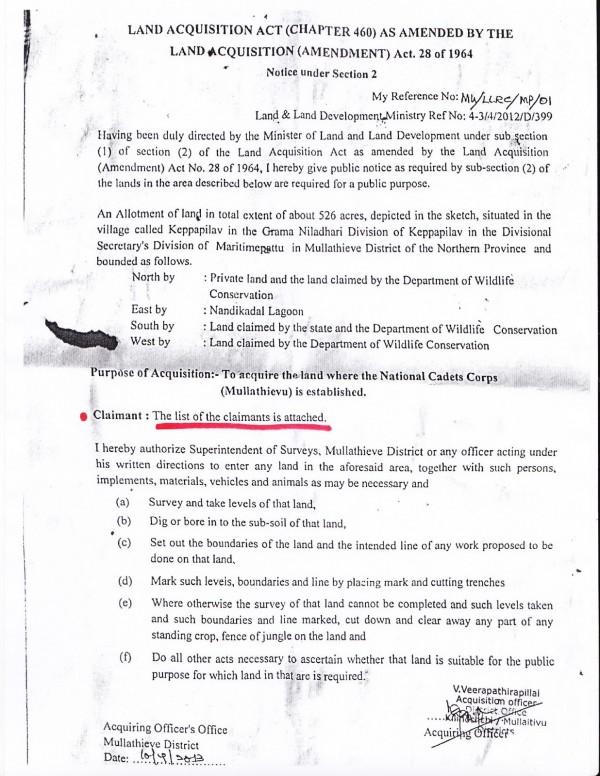

Community members from Keppapilavu have already suffered greatly, but it appears that the Government of Sri Lanka has decided to add more deception and unlawful behavior to its 2013 record. Last month the government issued a public notice stating that approximately 526 acres of land in Keppapilavu “are required for a public purpose.” (This means the government intends to expropriate the private lands of civilians). According to the English version of the notice, the expropriated land will be used to establish a “National Cadet Corps.” The notice is signed by an “Acquiring Officer” named V. Veerapathirapillai. Importantly, the letter is dated April 10, 2013

An Unconstitutional Land Notice

There are numerous problems with this notice.

The notice itself is unconstitutional, as it violates many aspects of the Land Acquisition Act (LAA). For starters – according to numerous reports by community members – the government has (unlawfully) backdated the document. This notice was not posted on April 10. Rather, community members have consistently mentioned that the afternoon of Wednesday April 24 was the first time that they had seen this document.[4]

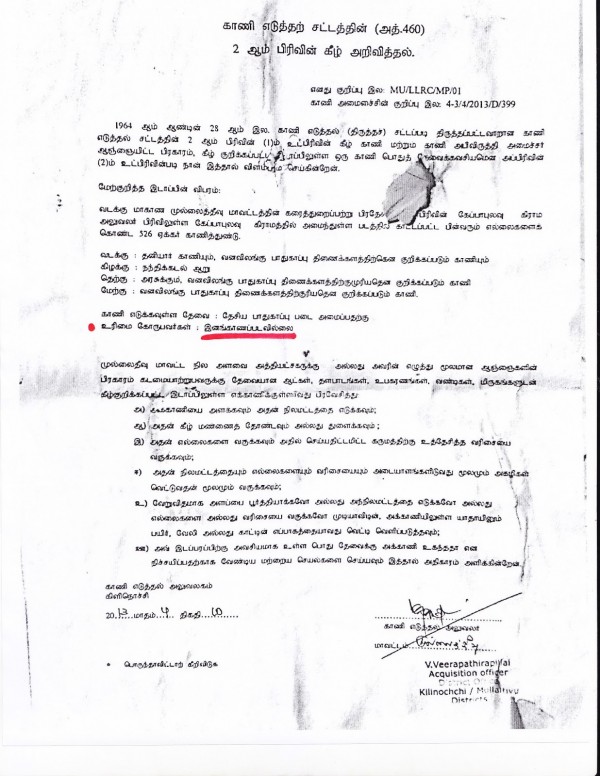

According to Section 2.2 of this act, the notice should be issued in all three languages and the state should clearly state the purpose for which the land is needed. The notice has been issued in all three languages. Yet – in the Tamil version of the notice – the Government of Sri Lanka has simply mentioned that a list of claimants is “unidentifiable.” However, according to the English and Sinhala versions of the notice, the claimants have been identified and their names have been provided. Nonetheless – in spite of what the English and Sinhala notices say – it does not appear that a list of claimant names has been provided in English, Sinhala or Tamil.

Again, as of the writing of this article, the government still has not made a claimants list available in any language.

Can the Government of Sri Lanka explain the reason(s) why – in a historically Tamil area such as Keppapilavu – this is happening?

Additionally, some readers may be left wondering why Government of Sri Lanka was unable to find a proper translator for a document of such importance.

Further, since the Sinhala and English versions of the notice state that the claimants have been identified and “The list of the claimants is attached,” the owners of the land should be allowed to identify their lands and estimate the value of their respective properties. Landowners should be allowed to enter Keppapilavu to do this, but that hasn’t happened on this occasion.

In addition – according to the LAA – if land is being acquired under circumstances like these it must be serving a public need or purpose; it should not simply be done for the benefit of the government. Even if land is being taken for national development, it must be for public purposes.

Since the land in Keppapilavu will purportedly be used by the security apparatus to establish a National Cadet

Corps, the government cannot credibly argue that these lands are being used for a public purpose. They are not. This legal precedent has been established in De Silva vs. Gamini Athukorale, Minister of Lands, Irrigation and Mahaweli Development and Another (1993), where Justice Fernando stated that “The purpose of the Land Acquisition Act was to enable the state to take private land, in the exercise of its right of eminent domain, to be used for a public purpose, for the common good; not to enable the state or state functionaries to take over private land for personal benefit or private revenge.”

Moreover, the LAA states that the Acquiring Officer should give community members at least seven days’ notice of his/her intention. What is more, the Acquiring Officer should give fourteen days’ notice regarding compensation. But this has not happened. Since the document was backdated, community members were not even able to file appeals which, under these circumstances, are prescribed in Sections 2.2 and 2.3 of the LAA. And, as of the writing of this article, no community members had been compensated – nor did any expect to be compensated given the inauspicious (and illegal) circumstances under which the notice was issued.

Land is still a very contentious issue in the North and East, but it looks like this is another example of government actors exacerbating a situation which is already difficult.

Conclusion

The Land Acquisition Act is a piece of legislation which the State is using to violate peoples’ fundamental rights – namely the right for people to own land. The Rajapaksa regime consistently talks about “resettlement” as one of its major achievements post-war. While hundreds of thousands of people have been relocated since the conclusion of war, the resettlement process remains far from complete. Moreover, having not even been allowed to return to the areas where they were once residing, tens of thousands are still dealing with protracted displacement. Having been “resettled” by Sri Lankan military personnel to a patch of jungle in Mullaitivu, community members in Keppapilavu are in dire straits. Yet, appallingly, it looks like the regime has now resorted to dishonest and illegal practices to further marginalize these conflict-affected people.

In Mahinda Rajapaksa’s post-war Sri Lanka, the sentence “the list of claimants is attached” in Sinhala or English is translated to the word “unidentifiable” in Tamil. Sadly, so much of this regime’s anti-Tamil agenda can be captured in a single land notice. Indeed, the war is over, but Rajapaksa’s glorification of an Extremist Sinhala Buddhist ideology continues – with no end in sight.

[1] Menik Farm was originally called Mannikam Farm.

[2] Menik Farm was created in early 2009.

[3] http://reliefweb.int/report/sri-lanka/united-nations-welcomes-closure-menik-farm-sri-lanka-concerned-last-remaining

[4] According to numerous reports by community members from Keppapilavu, the Grama Sevaka, the commanding officer of Keppapilavu Army Camp and five other members of the military arrived in Sooripuram (the “Model Village” where people from Keppapilavu have been relocated) and placed several land notices in the area. They came to Sooripuram in a military vehicle; this occurred between 12-1PM on April 24, 2013.

- Srilankacampaign.Org